[vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-sidebar-reviews”]

[vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-sidebar-reviews”]

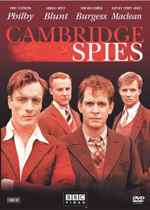

Cambridge Spies

2003, five-part series produced by BBC America

Director:

Starring: Directed by Tim Fywell

Reviewer:

Genre: Non Asian Movie Reviews

Rating:

Starring: Toby Stephens, Tom Hollander, Samuel West and Rupert Penry-Jones

Reviewed by Clement von Franckenstein

Rating (a 1 6 scale): 4.5

Peter Moffat, who has written a brilliant script for the series, had a huge task researching the story, as misinformation and deceit are a spys stock in trade. Luckily, Vasili Mitrokhin, a KGB archivist who had copied thousands of documents from about 1920 onwards, and had made a copy of each one for himself, smuggled his entire collection out of Russia into Britain in 1991, which proved invaluable to the writer.

What drove the four to embrace Communism? Fascism, via Hitler and Mussolini, was on the rise in Europe, people in 1934 did still not realize how evil Stalin was, the young revolution in Russia was growing in strength, and as no one in Europe was doing much to combat Hitler, they mistakenly came to believe that communism was the only way to fight Fascism.

Toby Stephens (the son of Dame Maggie Smith) who was the lead villain “Gustav Graves opposite Pierce Brosnan in “Die Another Day, plays Philby with a stiff upper lip and close to his chest, the way you would expect a master traitor to be. Whether lying to his boss, Lord Halifax, the British Ambassador in Washington (a rather bland James Fox) or trying not to fall in love with a beautiful German freedom fighter, he only lets glimmers of emotion escape.

The same cannot be said for Tom Hollander, who has a ball portraying Guy Burgess, by far the best-written part in the series. Burgess is a flamboyant and unabashed homosexual, described once as “the loudest spy in the history of espionage, with a gifted gob and wicked wit. After being Blunts on/off lover at Cambridge, he helped recruit Philby and Maclean. In one great scene he attacks an anti-Semitic toff with the verbal precision of a scalpel, knowing full well that even a bully will hesitate to hit a drunken and much smaller adversary. He worked for the BBC and MI5 while spying, then went to Washington to work under Philby, but was recalled for “serious misconduct. He warned Maclean via Philby that he was about to be arrested for treason, and fled with him to Moscow in 1951. His was the most tragic ending, as he could never adapt to Soviet life, and died from alcohol related illness in 1963. Hollander brilliantly brings this talented “rake to life, showing the sad lonely man under the booze and bravado, whose life was most vividly lived in his early twenties.

Rupert Penry-Jones captures well the agony of Donald Maclean, the most sensitive and tortured of the four spies. He felt he had betrayed his late father, Sir Donald Maclean, who had been a Liberal cabinet minister. Melinda his wife, who finally left him in Moscow and married Philby, knew all the time that her husband was a Soviet spy (via a KGB British operative named “Ada).

Maclean worked as a diplomat in Cairo, Paris and Washington D.C. whilst being Stalins main source of information about policy development between Churchill, Roosevelt and later Truman. While working on the Manhattan project, he reported the U.S. atomic bomb program to the Russians. After a “nervous breakdown in 1950, he fled with Burgess to Moscow in 1951 with MI5 snipping at his heels. In Russia he became a respected Soviet citizen, working for the Foreign Ministry. Penry-Jones shows how he veers between being warm and friendly to being drunk and difficult, again keeping a lot of emotion bottled up. Samuel West, who apparently did voracious amounts of research for his role of Anthony Blunt, strangely comes off as the least effective portrayal of the four. Like Burgess, for whom he acted as a “talent-spotter at Cambridge, Blunt was an overt homosexual. He was also a raging snob, who gloried in pomp, titles and his friendship with the Royal Family. West captures this well, but one would still like to have seen more of the man underneath the carefully manicured facade, and his performance is prone to being “one note.

Blunt served in British Intelligence in World War II while passing on information to the Russian Government. He helped Burgess and Maclean defect, and then confessed his treachery in 1964 (after Philby had left) in exchange for immunity. Queen Elizabeth, the wife of King George VI and the mother of the present Queen, had a soft spot for “upper-class queers and made him the Surveyor of the Queens pictures at Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle and Balmoral Castle in Scotland, a position he held from 1945-72. He was “unmasked as a spy by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1979 (a political move on her part to appease her Labor opponents) and had his 1956 knighthood annulled.

Cambridge Spies is the “best of British type of dramatic series that the English do exceedingly well. One is left with the feeling of how terribly lonely and depressing the life of a spy must be. The impact these four idealistic young traitors made between 1939 and 1945 was utterly devastating to the Allies, but they knew they could only trust in each other as true friends, and that eventually they would probably be unmasked. The script wonderfully balances history with the human side of these men. It explores how they justified their treachery, how it impacted their personal lives, and how they stood or fell together.